( excerpt)

|

In 1934, Henry Miller, then aged forty-two and living in Paris,published his first book. In 1961 the book was finally published in his native land, where it promptly became a best-seller and a cause célèbre. By now the waters have been so muddied by controversy about censorship, pornography, and obscenity that one is likely to talk about anything but the book itself.But this is nothing new. Like D. H. Lawrence, Henry Millerhas long been a byword and a legend. Championed by critics and artists, venerated by pilgrims, emulated by beatniks, he is above everything else a culture hero—or villain, to those who see him as a menace to law and order. He might even be described as a folk hero: hobo, prophet, and exile, the Brooklyn boy who went to Paris when everyone else was going home, the starving bohemian enduring the plight of the creative artist in America, and in latter years the sage of Big Sur.His life is all written out in a series of picaresque narratives inthe first-person historical present: his early Brooklyn years in Black Spring, his struggles to find himself during the twenties in Tropic ofCapricorn and the three volumes of the Rosy Crucifixion, his adventures in Paris during the thirties in Tropic of Cancer. In 1939 he went to Greece to visit Lawrence Durrell; his sojourn there provides the narrative basis of The Colossus of Maroussi.

Cut off by the war and forced to return to America, he made the yearlong odyssey recorded in The Air-Conditioned Nightmare. Then in 1944 he settled on a magnificent empty stretch of California coast, leading the life described in Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch. Now that his name has made Big Sur a center for pilgrimage, he has been driven out and is once again on the move.

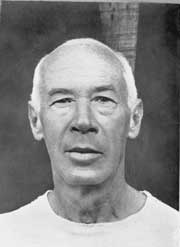

At seventy Henry Miller looks rather like a Buddhist monkwho has swallowed a canary. He immediately impresses one as awarm and humorous human being. Despite his bald head with itshalo of white hair, there is nothing old about him. His figure, surprisingly slight, is that of a young man; all his gestures and movements are young.His voice is quite magically captivating, a mellow, resonantbut quiet bass with great range and variety of modulation; he cannot be as unconscious as he seems of its musical spell. He speaks a modified Brooklynese frequently punctuated by such rhetorical pauses as “Don’t you see?” and “You know?” and trailing off with a series of diminishing reflective noises, “Yas, yas . . . hmm . . .hmm . . . yas . . . hm . . . hm.” To get the full flavor and honesty of the man, one must hear the recordings of that voice.

The interview was conducted in September 1961, in London.

—George Wickes, 1962

INTERVEW

- First of all, would you explain how you go about the actualbusiness of writing? Do you sharpen pencils like Hemingway, or anything like that to get the motor started?

H M - No, not generally, no, nothing of that sort. I generally go towork right after breakfast. I sit right down to the machine. If I find I’m not able to write, I quit. But no, there are no preparatory stages as a rule.

- Are there certain times of day, certain days when you workbetter than others?

H M - I prefer the morning now, and just for two or three hours. Inthe beginning I used to work after midnight until dawn, but that was in the very beginning. Even after I got to Paris I found it was much better working in the morning. But then I used to work long hours. I’d work in the morning, take a nap after lunch, get up andwrite again, sometimes write until midnight. In the last ten or fifteen years, I’ve found that it isn’t necessary to work that much. It’s bad, in fact. You drain the reservoir.

- Would you say you write rapidly? Perlès said in My FriendHenry Miller that you were one of the fastest typists he knew.

H M - Yes, many people say that. I must make a great clatter when I write. I suppose I do write rapidly. But then that varies. I can write rapidly for a while, then there come stages where I’m stuck, and I might spend an hour on a page. But that’s rather rare,because when I find I’m being bogged down, I will skip a difficult part and go on, you see, and come back to it fresh another day.

- How long would you say it took you to write one of yourearlier books once you got going?

H M - I couldn’t answer that. I could never predict how long a bookwould take: even now when I set out to do something I couldn’tsay. And it’s somewhat false to take the dates the author says he began and ended a book. It doesn’t mean that he was writing the book constantly during that time. Take Sexus, or take the whole Rosy Crucifixion. I think I began that in 1940, and here I’m still on it. Well, it would be absurd to say that I’ve been working on it all this time. I haven’t even thought about it for years at a time. So how can you talk about it?

- Well, I know that you rewrote Tropic of Cancer several times,and that work probably gave you more trouble than any other, but of course it was the beginning. Then too, I’m wondering if writing doesn’t come easier for you now?

H M - I think these questions are meaningless. What does it matterhow long it takes to write a book? If you were to ask that of Simenon, he’d tell you very definitely. I think it takes him from four to seven weeks. He knows that he can count on it. His books have a certain length usually. Then too, he’s one of those rare exceptions, a man who when he says, “Now I’m going to start and write this book,” gives himself to it completely. He barricades himself, he has nothing else to think about or do. Well, my life has never been that way. I’ve got everything else under the sun to do while writing.

- Do you edit or change much?

H M -That too varies a great deal. I never do any correcting or revisingwhile in the process of writing. Let’s say I write a thing out any old way, and then, after it’s cooled off—I let it rest for a while, a month or two maybe—I see it with a fresh eye. Then I have a wonderful time of it. I just go to work on it with the ax. But not always. Sometimes it comes out almost like I wanted it.

- How do you go about revising?

H M - When I’m revising, I use a pen and ink to make changes, crossout, insert. The manuscript looks wonderful afterwards, like a Balzac. Then I retype, and in the process of retyping I make more changes. I prefer to retype everything myself, because even when I think I’ve made all the changes I want, the mere mechanical business of touching the keys sharpens my thoughts, and I find myself revising while doing the finished thing.

- You mean there is something going on between you and the machine?

H M -Yes, in a way the machine acts as a stimulus; it’s a cooperativething.

- In The Books in My Life, you say that most writers and painterswork in an uncomfortable position. Do you think this helps?

H M - I do. Somehow I’ve come to believe that the last thing a writeror any artist thinks about is to make himself comfortable while he’s working. Perhaps the discomfort is a bit of an aid or stimulus.Men who can afford to work under better conditions often choose to work under miserable conditions.6

- Aren’t these discomforts sometimes psychological? You take the case of Dostoyevsky . . .

H M -Well, I don’t know. I know Dostoyevsky was always in a miserable state, but you can’t say he deliberately chose psychological discomforts. No, I doubt that strongly. I don’t think anyone chooses these things, unless unconsciously. I do think many writers have what you might call a demonic nature. They are always in trouble, you know, and not only while they’re writing or because they’re writing, but in every aspect of their lives, with marriage, love, business, money, everything. It’s all tied together, all part and parcel of the same thing. It’s an aspect of the creative personality. Not all creative personalities are this way, but some are.

- You speak in one of your books of “the dictation,” of beingalmost possessed, of having this stuff spilling out of you. How does this process work?

H M - Well, it happens only at rare intervals, this dictation. Someonetakes over and you just copy out what is being said. It occurred most strongly with the work on D.H. Lawrence, a work I never finished—and that was because I had to do too much thinking.You see, I think it’s bad to think. A writer shouldn’t think much.But this was a work which required thought. I’m not very good at thinking. I work from some deep down place; and when I write, well, I don’t know just exactly what’s going to happen. I know what I want to write about, but I’m not concerned too much with how to say it. But in that book I was grappling with ideas; it had to have some form and meaning, and whatnot. I’d been on it, I suppose, a good two years. I was saturated with it, and I got obsessed and couldn’t drop it. I couldn’t even sleep. Well, as I say, the dictation took over most strongly with that book. It occurred with Capricorn too, and with parts of other books. I think the passages stand out. I don’t know whether others notice or not.

- Are these the passages you call cadenzas?

H M - Yes, I have used that expression. The passages I refer to aretumultuous, the words fall over one another. I could go onindefinitely. Of course I think that is the way one should write all the time. You see here the whole difference, the great difference, between Western and Eastern thinking and behavior and discipline. If, say, a Zen artist is going to do something, he’s had a long preparation of discipline and meditation, deep quiet thought about it, and then no thought, silence, emptiness, and so on—it might be for months, it might be for years. Then, when he begins,it’s like lightning, just what he wants—it’s perfect. Well, this is the way I think all art should be done. But who does it? We lead lives that are contrary to our profession.

- Is there a particular conditioning that the writer can gothrough, like the Zen swordsman?

H M - Why, of course, but who does it? Whether he means to do itor not, however, every artist does discipline himself and condition himself in one way or another. Each man has his own way. After all, most writing is done away from the typewriter, away from the desk. I’d say it occurs in the quiet, silent moments, while you’re walking or shaving or playing a game or whatever, or even talking to someone you’re not vitally interested in. You’re working, your mind is working, on this problem in the back of your head. So, when you get to the machine it’s a mere matter of transfer.

- You said earlier there’s something inside you that takes over.

H M - Yes, of course. Listen. Who writes the great books? It isn’t wewho sign our names. What is an artist? He’s a man who has antennae, who knows how to hook up to the currents which are in the atmosphere, in the cosmos; he merely has the facility for hooking on, as it were. Who is original? Everything that we are doing, everything that we think, exists already, and we are only intermediaries, that’s all, who make use of what is in the air. Why do ideas, why do great scientific discoveries often occur in different parts of the world at the same time? The same is true of the elements that go to make up a poem or a great novel or any work of art.

They are already in the air, they have not been given voice, that’s all.They need the man, the interpreter, to bring them forth. Well, and it’s true too, of course, that some men are ahead of their time. But today, I don’t think it’s the artist who is so much ahead of his time as the man of science. The artist is lagging behind, his imaginationis not keeping pace with the men of science.

- How do you account for the fact that certain men are creative? Angus Wilson says that the artist writes because of a kind of trauma, that he uses his art as a kind of therapy to overcome his neurosis. Aldous Huxley, on the other hand, takes quite the opposite view,and says that the writer is preeminently sane, that if he has a neurosis this only adds to his handicap as a writer. Do you have any views on this subject?

H M - I think this varies with the individual writer. I don’t think you can make such statements about writers as a whole. A writer after all is a man, a man like other men; he may be neurotic or he may not. I mean his neurosis, or whatever it is that they say makes his “embracing planetary conjunction; topographical map of region and monuments and streets and cemeteries; fatal, or otherwise, influence of fields—according to type; Major Events; Dominant Idea; Psychological Pattern.”personality, doesn’t account for his writing. I think it’s a much more mysterious thing than that and I wouldn’t even try to put my finger on it. I said that a writer was a man who had antennae; if he really knew what he was, he would be very humble. He would recognize himself as a man who was possessed of a certain faculty which he was destined to use for the service of others. He has nothing to be proud of, his name means nothing, his ego is nil, he’s only an instrument in a long procession.

- When did you find that you had this faculty? When did youfirst start writing?

H M - I must have begun while I was working for the Western Union.That’s certainly when I wrote the first book, at any rate. I wrote other little things at that time too, but the real thing happened after I quit the Western Union—in 1924—when I decided I would be a writer and give myself to it completely.

- So that means that you went on writing for a period of tenyears before Tropic of Cancer appeared in print.

H M - Just about, yes. Among other things I wrote two or three novels during that time. Certainly I wrote two before I wrote the Tropic of Cancer.

- Could you tell me a little about that period?

H M - Well, I’ve told a good deal about it in The Rosy Crucifixion:Sexus, Plexus, and Nexus all deal with that period. There will be still more in the last half of Nexus. I’ve told all about my tribulations during this period—my physical life, my difficulties. I worked like a dog and at the same time—what shall I say?—I was in a fog. I didn’t know what I was doing. I couldn’t see what I was getting at. I was supposed to be working on a novel, writing this great novel, but actually I wasn’t getting anywhere. Sometimes I’d not write more than three or four lines a day. My wife would come home late at night and ask, “Well, how is it going?” (I never let her see what was in the machine.) I’d say, “Oh, it’s going along marvelously.” “Well, where are you right now?”

Now, mind you,maybe of all the pages I was supposed to have written maybe I had written only three or four, but I would talk as though I’d written a hundred or a hundred and fifty pages. I would go on talking about what I had done, composing the novel as I talked to her. And she would listen and encourage me, knowing damned well that I was lying. Next day she’d come back and say, “What about that part you spoke of the other day, how is that going?” And it was all a lie, you see, a fabrication between the two of us.

The Art of Fiction No. 28

Interviewed by George Wickes Summer-Fall 1962

|